Last week on the preeminent social media site, Bluesky, a spirited debate broke out between Matt Darling and seemingly most of the site’s other users. The point of contention was how many gig workers there are in America. Darling pointed to data from the BLS that he said indicated the number of gig workers had declined since the 1990s. This was met with shock and outrage by others who thought that, with the rise of Uber, DoorDash, and other app-based employment options, there’s no way this could be true. This argument was set in the context of the larger debate over whether “the economy” is good, actually, or bad, actually. Darling and others come down on the side of: the economy is mostly fine, but people’s perceptions have become warped by the media they consume. Others, typically to Darling’s left, dispute the assertion that things are fine vigorously.

Darling based his argument on a BLS report that shows that 4.3% of the employed population held a “contingent” job in 2023, down from 5% in 1995. Contingent jobs “are those that people do not expect to last or that are temporary,” according to the BLS. A subset of the debate was whether an Uber driver would in fact respond in the affirmative when asked if he had a contingent job by a surveyor. Various Blueskyers argued that this hypothetical Uber driver would not respond in the affirmative, because why would he not expect his job as a driver to last? Further complicating the matter is the note at the bottom of the BLS blog noting that they had asked additional questions on app-based jobs but that data had not yet been released.

If you believe that an Uber driver would not necessarily say that he was a contingent worker if asked in a survey, but still wanted to get a grasp on the number of gig workers, you might instead point out that the BLS reports also show that the share of the employed who are independent contractors was slightly higher in 2023 (7.4%) than 1995 (6.7%). Because Uber drivers are defined by the company as independent contractors rather than employees, this would seem to run counter to Darling’s argument that gig work is less prevalent now than in the 1990s. That being said, a 0.7 percentage point increase is quite small either way.

I decided to try my hand at figuring out how many gig workers there are, and how that number has changed since the 1990s. Unfortunately, my usual source of CPS data, IPUMS, does not include the variables on second jobs, which are important when looking at anything related to gig work. Instead, I had to use the full Census files, which are much more unwieldy than the IPUMS data. So instead of using data from every month, I selected four months to look at between 1995 and now.

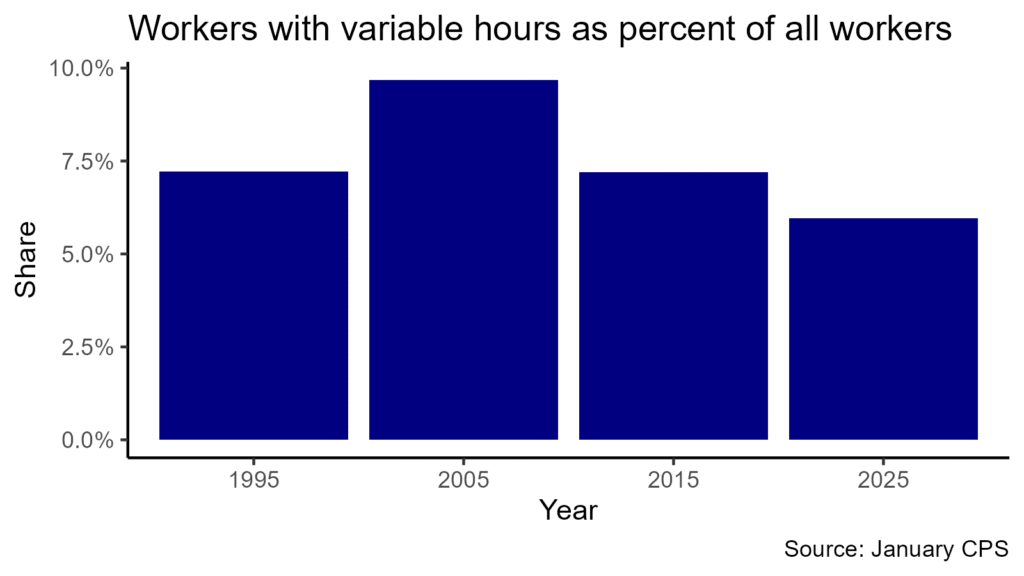

I defined a gig worker as any worker who reported that their usual hours worked per week varied, in either their primary job or secondary job (if applicable). I also wanted to only include self-employed workers, but the variable with this information for secondary jobs is not available for most people. I also realize that there are probably plenty of gig workers who work the same amount of hours each week, but seeing as this blog is neither my primary nor secondary job, looking at workers with varying hours is the best I can do.

As it turns out, using my definition of gig worker, the share of gig workers as a percentage of all workers has fallen since 1995, from about 7% to just under 6%. This tracks somewhat closely with the BLS report on contingent workers. I have to admit, I am a little surprised at this finding, as it really does seem like gig workers are everywhere these days. It’s possible that is because they are in more visible jobs, like Uber driver or food delivery, compared to the 1990s. I wanted to investigate this question too, but since occupation data was only available for people’s primary jobs, I was not able to. In any case, it will be interesting to see what the BLS reports when they release their app-based employment numbers. Until then, we’ll just have to keep arguing on Bluesky.

0 Comments